Must-read recap: The New Lede's top stories

Cattle feedlot pesticides may threaten Texas wetlands, pregnant mothers' PFAS exposure may affect adult sons' sperm quality, and a new PFAS exposure scoring method.

Pesticides from cattle feedlots may threaten Texas wetlands

Across northwest Texas, from the panhandle south past Midland, nearly 20,000 shallow, watery basins dot the landscape. Locals call them mud holes, buffalo wallows, or lagoons, but they are technically known as playas. As oases in the landscape, these wetland areas act as recharge points for the Ogallala Aquifer and play a critical role in sustaining life in northwest Texas.

Another mainstay of northwest Texas are the cattle farms that sprawl across the flatland. Texas boasts 14% of the nation’s cattle — about 13 million animals — and cattle operations make up more than half the market value produced by Texas farmers, bringing in billions of dollars in sales each year.

But now, new research is adding evidence that pesticides used at cattle feed lots to protect animals from potentially disease-carrying insects may be posing a dire threat to the ecosystems of the playas.

Researchers from Texas Tech University said in a paper published in Environmental Pollution that insecticides known as pyrethroids were detected in sediment from 75% of the state’s playa wetlands. The concentration of pyrethroids detected correlated with the wetland’s proximity to a feedlot — the closer the wetland was to a feedlot, the higher the pyrethroid concentration in the sediment.

Researchers say the pesticide concentrations found were toxic to two invertebrate species found in playas. Invertebrates are often used as “bioindicators” the health of other animals in an ecosystem. Since other wildlife rely on playa invertebrates for food, the toxic effects could eventually impact the stability of the whole playa ecosystem.

Amanda Emert, the lead author on the paper and a graduate student at Texas Tech University, said the levels of pyrethroids they found in the sampling were “unexpected.”

Additionally, said Emert, since their study analyzed the pyrethroids separately, the results don’t account for possible interactions between chemicals, which could have a more harmful effect. The results, therefore, are probably an underestimate of potential toxicity to wildlife, according to Emert and Smith. (Read the rest of the story.)

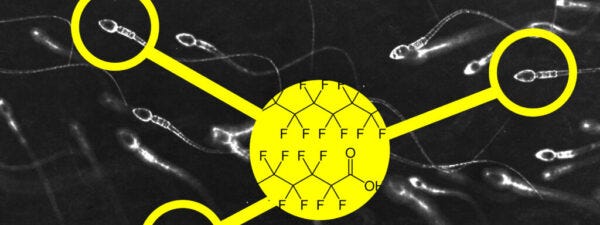

Pregnant mothers’ PFAS exposure may affect adult sons’ sperm quality

Exposure to toxic PFAS chemicals during pregnancy potentially can affect the reproductive health of male children after they reach maturity, researchers reported last month.

In a study that included more than 800 young Danish men, researchers found associations between lower sperm quality when the men reached young adulthood and levels of PFAS in their mothers’ plasma during early pregnancy.

The findings, which were published October 5 in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives, suggested that combined maternal exposure to seven of these toxic “forever chemicals” was associated with male offspring who grew up to have lower sperm concentrations, lower total sperm counts, and higher proportions of sperm that cannot travel normally (or at all).

The scientists identified one particular PFAS, perfluoroheptanoic acid (PFHpA), as the main contributor to all three effects on sperm quality, although they caution that more research is needed to confirm whether the chemical really has an outsized effect.

“This could mean that PFHpA is very potent or has a higher placental transfer than the other PFAS,” said Sandra Søgaard Tøttenborg, a professor at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark and an author of the study. “It could also be a chance finding, considering the multiple comparisons we’ve made and the low concentrations of PFHpA. Before we have other studies to compare with and a more evidence on the mechanisms, we don’t put too much emphasis on this finding.”

Male sperm count and quality are generally on the decline. A 2017 analysis showed a 50-60% decline in sperm concentrations in men from around the world from 1973 to 2011, while a 2019 study found that the proportion of men in two countries with a normal number of motile sperm dropped by about 10% from 2002 to 2017.

Pheruza Tarapore, an environmental and public health sciences researcher at the University of Cincinnati who was not involved in the study, thinks that endocrine disruptors including bisphenol A (BPA), bisphenol S (BPS), and PFAS may help explain this concerning phenomenon. (Read the rest of the story.)

New PFAS exposure scoring method could speed research on health effects

Researchers have developed a new statistical tool they say could speed up research on the health effects of exposures to toxic “forever chemicals” that are commonly found in an array of consumer products.

In a study published last week in Environmental Health Perspectives, researchers from the Mount Sinai Medical Center and Johns Hopkins School of Public Health presented a new tool that offers PFAS researchers a way to compare total exposures to PFAS across scientific studies. The tool may provide researchers a more effective method to study these persistent toxins.

PFAS, an acronym for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are a class of thousands of chemicals commonly used in non-stick cookware, food packaging, and waterproof clothing. The chemicals have been linked to certain cancers and reproductive issues.

Studying chemical mixtures is crucial to public health research, since people are exposed to many chemicals—including many types of PFAS—at once in their daily lives. But most studies that focus on toxic chemical mixtures only study those effects in relation to specific health outcomes; for example, a study might determine a chemical’s effect on blood pressure, or heart disease. Additionally, studies might measure different types of PFAS chemicals. That makes it hard for environmental health researchers to compare data.

Researchers proposed a fix to this problem by developing a calculator tool that can estimate total PFAS exposure burden using just a few measurements of PFAS exposure. According to Shelley Liu, lead author on the study and a professor at the Ichan School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Medical Center, the calculator tool is the first of its kind in the environmental health field.

Liu describes studying PFAS exposure burden as an iceberg: The types of PFAS scientists measure are the tip of the iceberg, but more exposure likely lurks below the water. Her team’s tool, created using data from the National Health Nutrition and Examination Survey (NHANES), helps to estimate the total exposure—the whole iceberg. Scientists can use it to assign total exposure “scores” to individuals in environmental health studies, making comparison across studies and analysis of disparate sets of data more feasible, said Liu.

“It’s okay if we don’t measure the full set of PFAS,” said Liu. “We can still use [the calculator tool] to estimate PFAS burden across studies. (Read the rest of the story.)

Thanks so much for these articles. I've been trying to get this information out - and more regarding pesticides and industrial chemicals - since the 90's, but people really do not want to know about this because it would man they'd have to change something in their lives - - like using pesticides on their crops and gardens.

Please keep up the good work.

Also, and no one wants to say this either, the huge number of males identifying at least in part as female is, to my mind, because of these estrogen-imitating chemicals many of which have been in their mothers' bodies for decades now. Very sad and this will clearly not end well.

Also females with endometriosis - now up to 1 in 10 (likely an undercount), which is an awfully painful disease which often makes the women sterile can be, I believe, attributed to these chemicals and many others in use in everyone's lives. Slow-moving catastrophes for not only humans, but all other creatures, as well.

This has been going on for decades - frogs, fish, alligators, and so many more, but the powerful monied interests will not allow this information to reach the general public, and too many scientists are afraid for their jobs to speak the truth.

So, thanks again. Much appreciated.